Problem Statement

The idea of autonomously operating (“self-learning”) information processing agents has recently gained traction in the AI research community. Depending on context, the development of these agents involves some hard challenges including the need for the agents to be capable of learning specific goals in dynamic real-world.

In this project we investigated a novel solution approach to the design of autonomous agents. We recognize that any “intelligent” autonomously operating agent needs to be minimally capable of realizing three tasks:

- Perception: online tracking of the state of the world.

- Learning: making updates to its world model in case the agent’s model poorly predicts real-world dynamics.

- Decision making: agents should be able to act onto (“control”) the world in order to make an impact on the future dynamics of the world.

There exists a powerful computational theory for how biological agents accomplish the aforementioned task palette. This theory, which is called Active Inference, relies on formulating all tasks (perception, learning and control) as (automatable) inference tasks in a (biased) generative model of agent’s sensory inputs [3].

In order to assess the feasibility and capabilities of active inference as a framework for synthetic agents in a real-world setting, we developed a ground-based robot that needs to learn to navigate to an undisclosed parking location. The robot can only learn where to park through situated interactions with a human observer who is aware of the target location.

Methods and Solution Proposal

Figure 1 shows the robot that was used in this project. The Boe-Bot robot by Parallax comes equipped with wheels and continuous rotation servomotors [5]. The computational backbone relies on an Arduino Uno to gather sensor signals and the Active Inference agent was coded in the Julia programming language on a Raspberry Pi4-based Linux environment.

The robot that was used in the current study.

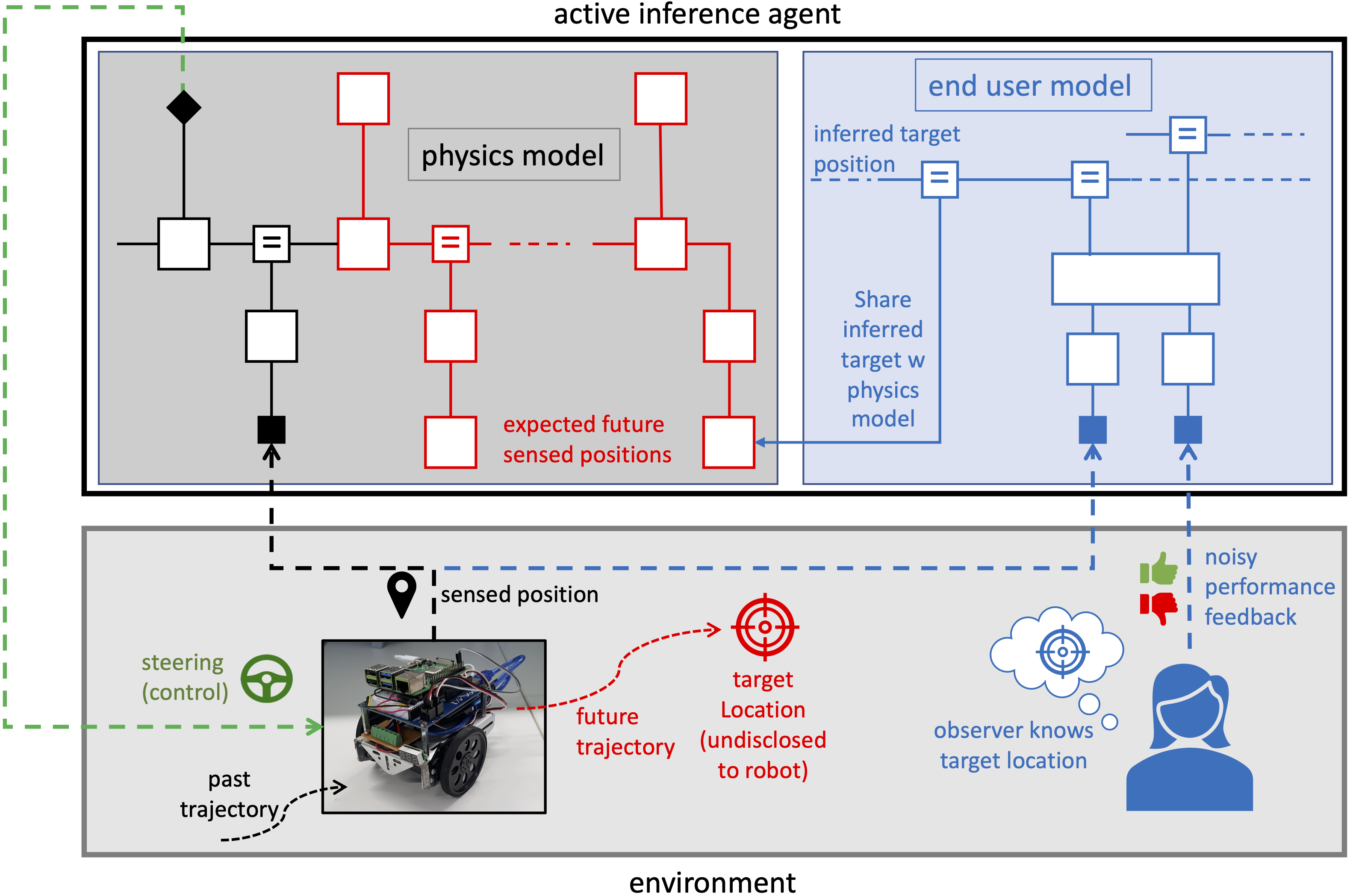

Figure 2 shows the information processing architecture of the active inference agent and its environmental interactions. The environment consists of a robot and an observer. The robot needs to park at a location that is initially unknown to the robot’s steering agent (called “physics model” in the figure), but the observer does know where to park. At any time, the observer can express binary (thumbs up or down) performance appraisals to the agent on the basis of her assessment on how well the robot is executing its parking task. The agent’s task is to learn the target parking location from these appraisals and steer the robot to this location.

Information processing architecture of agent and its environmental interactions.

The agent is constructed as an Active Inference agent. The central tenet of Active Inference is that every task, including perception, learning and decision making, is framed as a Bayesian inference task in a (biased) generative model of the agents sensory inputs, which comprise (noisy) measurements of the robot’s position and the observer’s appraisals. The agent’s generative model consists of two interacting sub-models: one model for predicting the robot’s position and the other model for the observer appraisals. The agent is capable of simulating the physical model forward in time so as to predict where the robot will be located as a function of its steering signals. Initially, the physics model has no expectations about where to park. However, the agent’s observer model infers desired future locations from the appraisals and relays this information to the physics model. Thus, as time progresses the physics model acquires more specific information about desired future positions. Through Bayesian inference (technically: variational inference), the agent is now capable to infer the steering signals that are needed to fulfill its expectations about (desired) future locations. Crucially, all information processing in this agent is framed as a variational inference task, which is automatable with modern probabilistic programming tools.

Various generative models were created, iteratively refined and verified in simulations and then ported to the robot. Inference algorithms were automatically generated using probabilistic programming toolboxes such as ForneyLab [1] and Turing [4].

Results

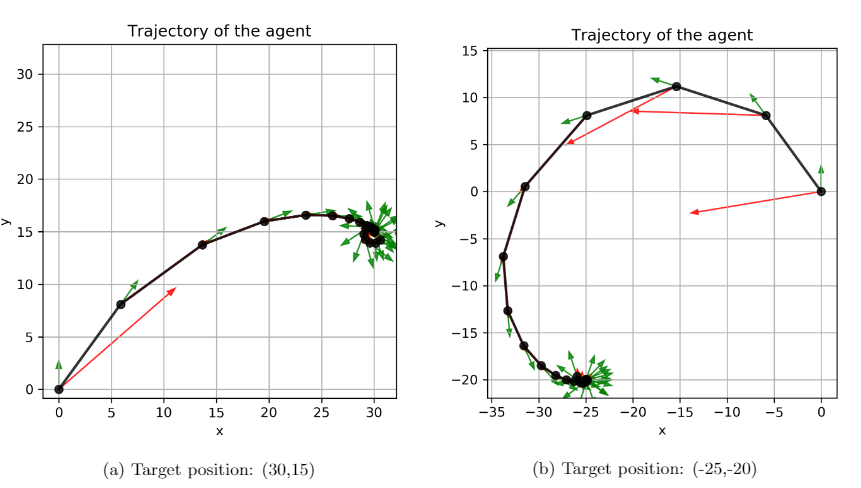

Figure 3 depicts two examples of how the robot navigates on a 2D plane. At each time step, the agent observes the robot’s position and orientation and infers the next steering action in terms of motor velocities for both wheels.

Robot navigation examples with binary performance appraisals by an observer in-the-loop.

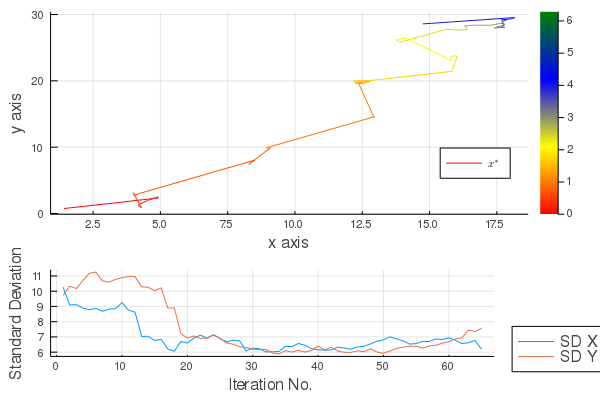

Figure 4 shows a typical evolution of the agent’s belief about the target location.

Evolution of agent's belief about target position for trial in Figure 3a.

Active inference agents also seem to be robust when they are subjected to environmental perturbations. The video below demonstrates how the active inference agent immediately corrects a severe manual interruption and continues its path towards the target location.

These experiments provide support for the notion that active inference is a viable method for constructing synthetic agents that are capable of learning new goals in a dynamic world. More details about this project are available in a MSc thesis [2].

References

- Marco Cox, Thijs van de Laar, and Bert de Vries. A factor graph approach to automated design of Bayesian signal processing algorithms. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning, 104:185–204, January 2019.

- Burak Ergül. A Real-World Implementation of Active Inference. Master’s thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, April 2020.

- Karl Friston. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2):127–138, 2010.

- Hong Ge, Kai Xu, and Zoubin Ghahramani. Turing: a language for flexible probabilistic inference. InInternational Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, AISTATS 2018, 9-11 April 2018, Playa Blanca, Lanzarote,Canary Islands, Spain, pages 1682–1690, 2018.

- Parallax Inc. Robot shield with arduino., 2020. Accessed: 2020-04-08.