Solving the Wrong Problem

When you need to solve a problem and you only have a vague description of that problem, the best strategy is to first gather more information about what the problem really is, rather than deeply investing in the design of a sophisticated solution. A great example of this approach to problem solving was described by Aza Raskin in his blog on the development of the first human-powered airplane to cross the English channel. Paul MacCready, who lead the successful development of said human-powered airplane, phrased it as “The problem is we don’t understand the problem”.

Fail fast, fail often

How do you find out what the problem is? MacCready built planes, crashed the planes and rebuilt new prototypes in a matter of hours. In other words, he learned about the problem by going through as many test runs as fast as possible. The design focus was more on how to rebuild planes in just a few hours than on building the perfect plane. Today, we would call this the ‘fail fast, fail often’ approach.

Hearing aid (HA) design is also a problem with lots of uncertainties. When engineers design HA algorithms, they don’t know yet who the patient will be nor her specific hearing loss problems. They also don’t know in what acoustic environments she tends to spend time and what her listening preferences are.

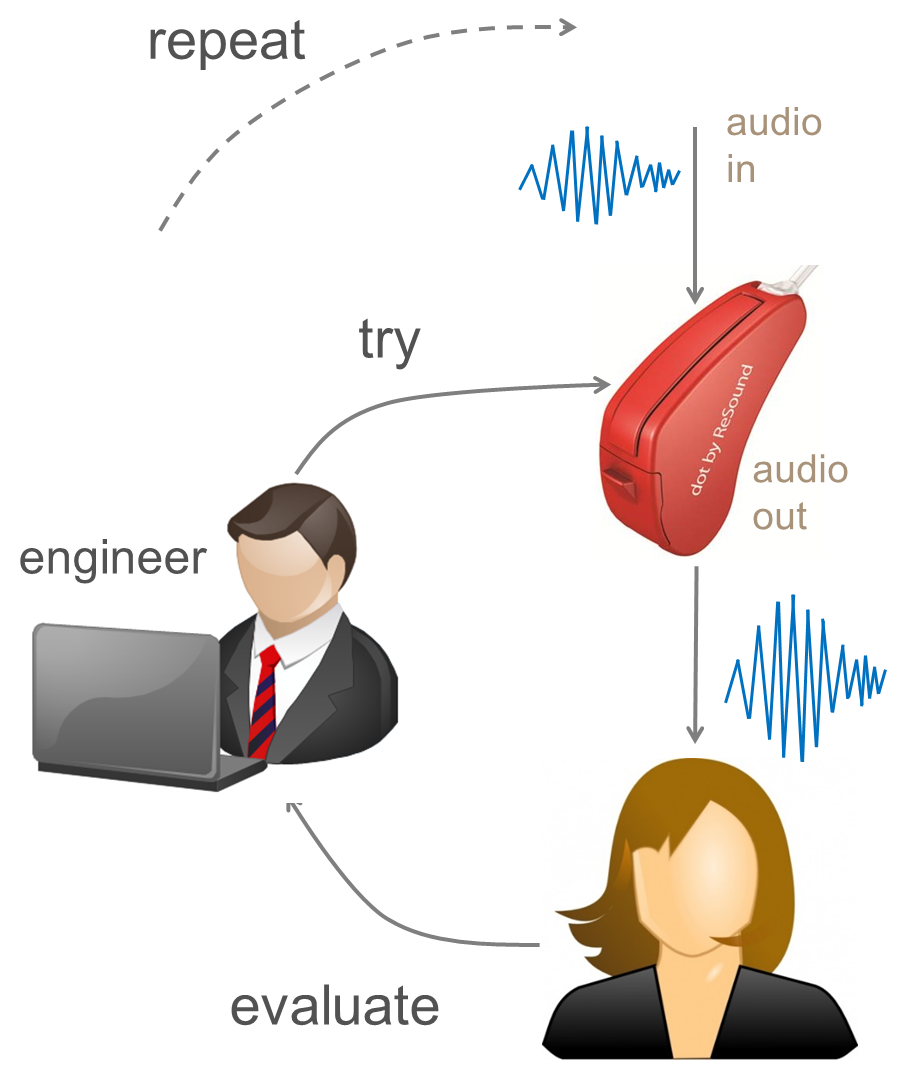

Still, both the HA industry and academic researchers on HA algorithms by and large focus their efforts directly on designing the ‘best’ HA solution. Engineers design HA algorithms and tinker with those algorithms in an off-line setting (at their desks) in an effort to improve those algorithms on the basis of patient feedback, see Fig.1. Each design iteration for a HA module (such as a noise reduction or feedback cancellation algorithm) with a human engineer in-the-loop often takes years.

Our approach

Our approach to HA algorithm design is focused on getting algorithm design loops down to hours or even seconds, thus facilitating learning about the problem as fast as possible. Like MacCready, our design loops comprises fast iterative testing of solution proposals, so problem definition development goes hand-in-hand with the development of solutions.

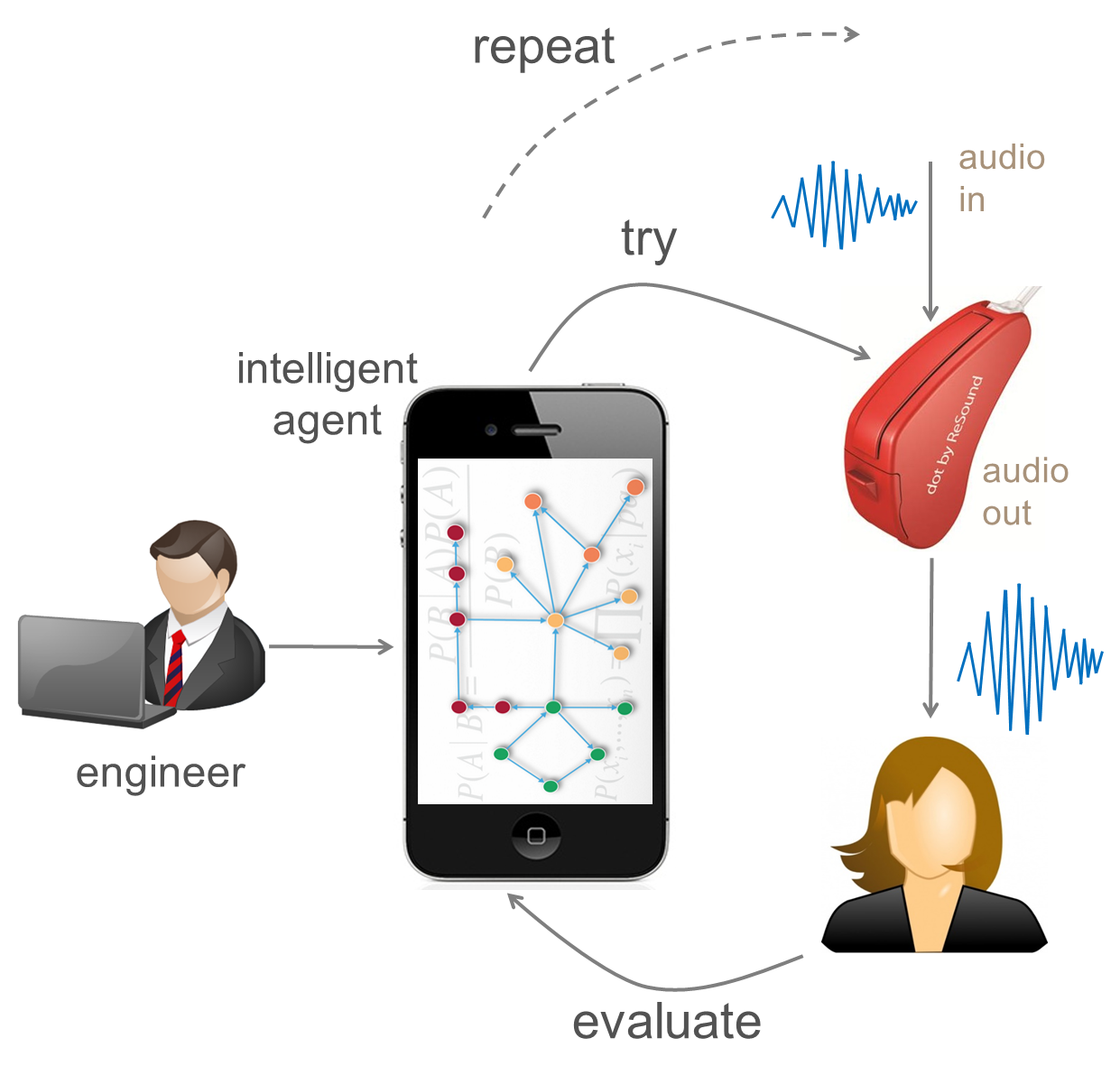

In order to scale down a design iteration from years to seconds, we cannot afford to have a human engineer in the design loop. Rather, in our approach, we (the engineers) aim to design an automated HA designer instead of the hearing aid algorithm itself, see Fig.2.

The task of the automated designer, which in the technical literature is called an intelligent agent (IA), is to propose an interesting alternative algorithm each time when the patient is not happy, under in-situ conditions. This is a monumental task that involves learning from experiences and rational decision making under uncertainty. We take a fully Bayesian (= probabilistic) approach to designing such intelligent agents (see also our mission page).

The broader picture

Next to hearing aid design, Bayesian intelligent agents may have applications to solving problems whenever we don’t have a clean problem description. Most interesting problems are of this nature. In our team, the focus lies on applications to hearing aids and hearables for health and fitness monitoring and coaching, but we are also interested in other wearable smart computing applications.

Finally, the idea of focusing on fast iterations as a fundamental design principle has permeated various related disciplines. In the context of software design, Sandi Metz summarizes the idea as follows (pg.16 in Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby, 2012):

Design is more the art of preserving changeability than it is the art of achieving perfection.